New technologies in digitisation are paving the way for more accurate and visually descriptive preservation of cultural heritage collections. Of these new technologies, NZMS is embracing structured light 3D scanning to capture objects 3-dimensionally, delivering multiple viewpoints and allowing for an increased sense of tangibility – superior to a typical photograph. NZMS’s scanner of choice is the handheld GoSCAN50 that uses projected flashing lights to capture both the texture and shape of an object as it is reflected into the scanner’s camera.

NZMS digitisation technicians, Ella Beckett and Nigel Roper, recently visited the Air Force Museum of New Zealand (AFM) located in Christchurch to test the 3D scanner and create images of some of the aircraft in the collection. The AFM is the national museum for the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) and New Zealand military aviation, housing a large number of historically significant aircraft and welcomes over 150,000 visitors a year. Ella and Nigel spent two days on site equipped with the GoSCAN50 and were given access to three aircraft: an Aerospace CT/4B Airtrainer, the fuselage of a Consolidated Catalina flying boat, and a Seasprite helicopter.

Ella Beckett scanning the CT/4B Airtrainer

Ella Beckett scanning the CT/4B Airtrainer

In its heyday the bright yellow Airtrainer was the primary pilot training aircraft of the RNZAF and was in service for almost 40 years. As the only aircraft operated by the RNZAF to have been designed and manufactured in New Zealand, it is an important piece of aviation history and a prime subject for digitisation. The Airtrainer presented many challenges in 3D scanning, especially when attempting to scan the nose and propeller of the aircraft. Unfortunately, the reflective coating over the black sections of the propeller were completely invisible to the scanner and this meant the scan could not be completed. As a learning opportunity this was a success because we were able to push the limitations of the scanner and determine the exact parameters of what it could do.

The Airtrainer’s cockpit was also scanned and proved to have a far more favourable outcome. The resulting image was made up of eight scans merged together and took a total of 23 hours to complete including post-processing. To capture the inside of the cockpit, our digitisation technicians needed to get creative: one operator stood on the wing of the aircraft leaning into the cockpit, while the other stood on the ground holding a laptop, external battery, and cords at waist height so the screen could be seen by the first operator on the wing.

Some of the scan from the cockpit of the CT/4B Airtrainer.

Some of the scan from the cockpit of the CT/4B Airtrainer. Cockpit of the CT/4B Airtrainer.

Cockpit of the CT/4B Airtrainer.

3D digitisation can be especially beneficial for large objects, such as aircraft, because it can improve its accessibility. Museums and art galleries are frequently revising how they might make their collections more accessible to the public, particularly those visitors who cannot view objects in a traditional manner due to constraints such as mobility. By providing 3D images of objects, people who might not have otherwise had the opportunity will be able to interact with it digitally — viewing it up close and from multiple angles in order to appreciate its form and better consider its unique history.

“I like the idea of 3D digitisation enabling interpretation and access, especially with things that are hard to reach, or aren’t safe for people to climb inside. You can see it from different angles, and you don’t even have to be in the same place as the object —you can view it from home.” – Ella Beckett, Digitisation Technician, NZMS

Of the three, the most successful scan came from the Catalina flying boat which is currently undergoing a detailed conservation programme at the AFM. Atmospheric conditions in its previous storage location meant that the aircraft suffered surface corrosion and remedial work needed to be undertaken to prevent further damage. The Catalina has a varied and turbulent history — it saw US military service at the end of World War Two, it was used for commercial purposes by Cathay Pacific in Hong Kong, it was part of the Sunbird Service in Papua New Guinea for Trans-Australia Airlines, and finally it was used as an airport fire dump for crash rescue practice in Port Moresby.

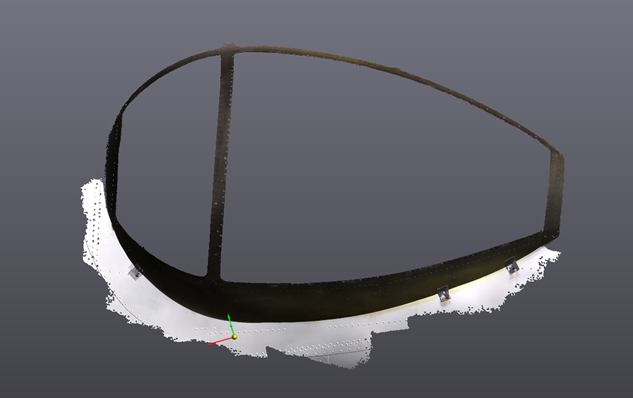

Outcome of the blister window 3D scan for the Catalina flying boat.

Outcome of the blister window 3D scan for the Catalina flying boat.

“When we requested a 3D scan of the Catalina window frame, our intention was to experiment with the outcome and determine its potential use for the restoration project – this is an ongoing process. Traditional methods and skills for creating parts are increasingly hard to come by, the original machinists are aging, and there is a risk their unique skills could be lost with them. This is a huge issue for accurate conservation and restoration – 3D scanning might be the answer.” – Alex Rutherford, Exhibitions Technician, Air Force Museum

In our contemporary society, where people are frequently preoccupied with computers, smart-phones and tablets, digital formats are increasingly providing the best levels of engagement. 3D scanning provides a unique and exciting way for the public to view collections online. Immersive environments can be created with 3D scanning in the form of virtual reality experiences which enhance people’s ability to interact with and discover an object. The 3D images from aircraft at the AFM can allow visitors a chance to view aircraft from inside cockpits, or other locations, which have in the past been unattainable.

As with any new technology, 3D scanning has limitations, but these will be continually improved with time and testing.

“I’m excited by the prospect of the technology for 3D scanning getting better — structured light scanning is such a new technology and it can only get better. Limitations that we’ve found around difficult materials including shiny objects or tiny details will improve in time and as the technology evolves.” – Ella Beckett, Digitisation Technician, NZMS

At NZMS we believe that 3D scanning can provide the Cultural Heritage sector with the tools to accurately conserve irreplaceable material in the form of digital 3D data. It allows for alternative preservation and archive management, improves the accessibility of collections, expands opportunities for research and learning, and it provides new ways to further community engagement.

Our testing at the Air Force Museum of New Zealand was a step towards realising the true capabilities of 3D technology and discovering how it can be incredibly beneficial to our clients.

If you think your 3D collection could benefit from 3D digitisation, get in touch with our team today