ANZAC day, 25th of April, is a National Day of Remembrance for both New Zealand and Australia. It conjures a shared heritage by marking the anniversary of troops landing on the Gallipoli Peninsula in Turkey, 1915. A devastating loss of life was experienced during this battle, but it also cultivated a strong sense of nationhood for both countries. Today ANZAC services more widely commemorate anyone who has served or died in wars, conflicts, and peacekeeping operations. It also aims to acknowledge the contribution and suffering of all those who have served for New Zealand and Australia.

Preserving our nation’s cultural heritage and the items that tell people’s stories is an important part of respecting our history and learning from the past — NZMS recently had the opportunity to play an integral part in ensuring New Zealand’s wartime history was preserved by digitising Dunedin Public Libraries’ collection of WWII troopship magazines.

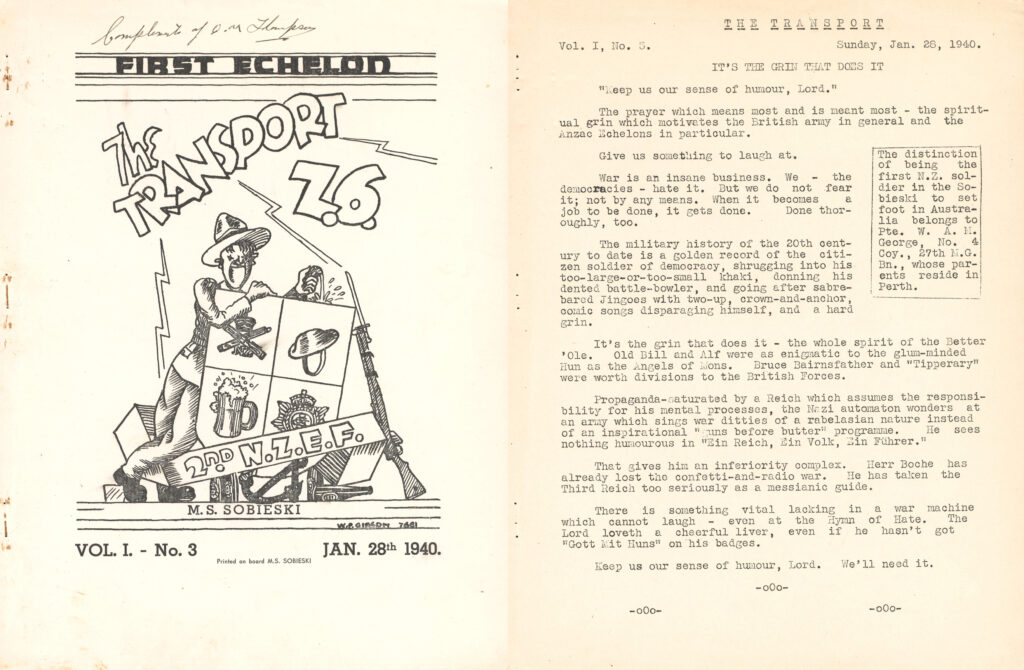

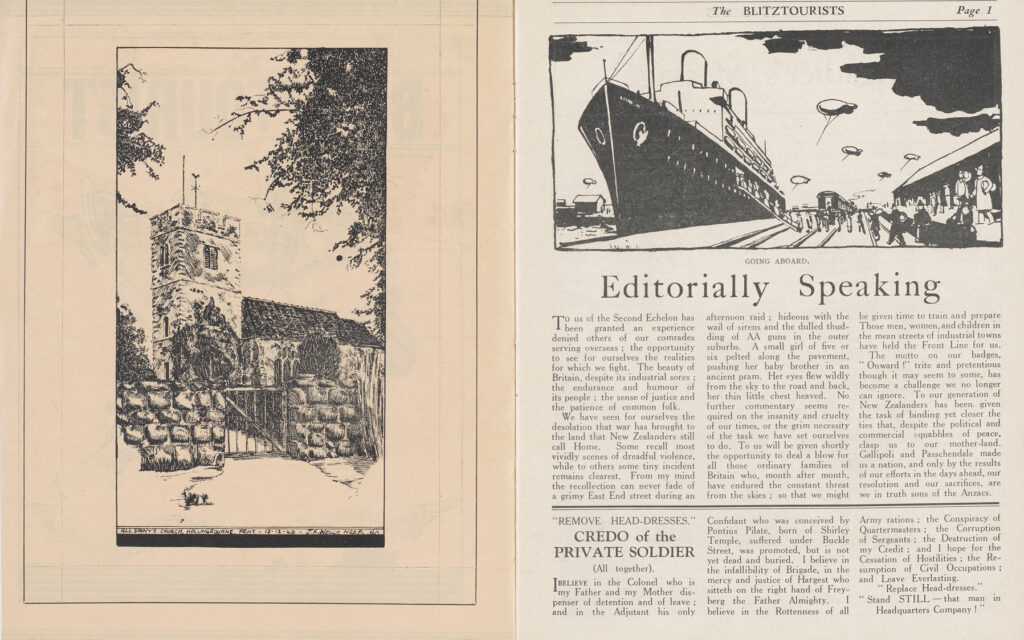

The need for transportation to other continents during both world wars meant that troopships are a prominent feature of New Zealand’s military history. Magazines were often produced on board by weary soldiers wanting to foster community spirit and fend off boredom during the long voyages. Nowadays, these magazines serve as poignant reminders of the often cruel and perilous nature of war, while also highlighting the resilience of human spirit, shown through shipboard humour and a willingness to share in a sense of comradery.

Dunedin Public Libraries’ Collection

The collection of troopship magazines held by Dunedin Public Libraries was started in 1915 by the City Librarian, W. B. McEwan. He was aware of the cultural significance of these ephemeral print items and sent out a public request for donations of the magazines, which at that time spanned those created during WWI. He recognised that the magazines reflected the attitudes and mood of soldiers heading off to war and are a record of life on board troopships — something that likely isn’t preserved in any other form. Dunedin Public Libraries’ troopship magazine collection has grown to include material that has not only been published at sea, but also those created in military hospitals, prisoner of war camps, and during active service. It now spans publications from WWI, WWII, and the South African War.

The collection has not been comprehensively researched, especially the WWII component, but digitisation will help make the collection more accessible to researchers. While there are other similar collections in New Zealand, the Dunedin Public Libraries’ collection is certainly one of the largest, boasting over 379 volumes. A substantial proportion of these magazines are very rare and hold a unique position in the collectable fields of militaria and documentary war material — this makes it even more important that they are properly digitised to ensure they can be accessed online, allowing the originals to be stored away safely and preserved. The troopship magazines can be viewed on Dunedin Public Libraries’ Scattered Seeds.

Creating a Worthy Replica

NZMS digitised Dunedin Public Libraries’ collection of troopship magazines using a Phase One camera — selected because of its ability to photograph in high resolutions and the incredibly detailed, clean images it produces. It is the perfect tool for cultural heritage digitisation which aims to produce a true to life representation of the original. While the collection is fragile because of its age, most volumes were in a remarkably good condition, and our team were able to successfully digitise all the magazines to Dunedin Public Libraries’ specifications.

Some of the magazines were bound together into a hardcover book — unfortunately this meant the binding is quite tight and text often ran very close to the spine of the book, or was even cut off in some places. Our team had originally planned to capture the items as full page spreads, but this needed to be revised once the tight binding was discovered. To digitise as much of the text as possible, each page was photographed individually, which meant the book could be angled in a way that allowed the camera to capture any text that curved into the spine.

NZMS provided the Library with a range of outputs from the digitisation, including preservation master files, unedited 16-bit tif images for long-term storage and preservation; modified master files, 8-bit mastered tif images for high-resolution viewing; and access files, multi-page PDF’s of each volume suitable for online viewing and downloading.

Wartime Cultural Artefacts

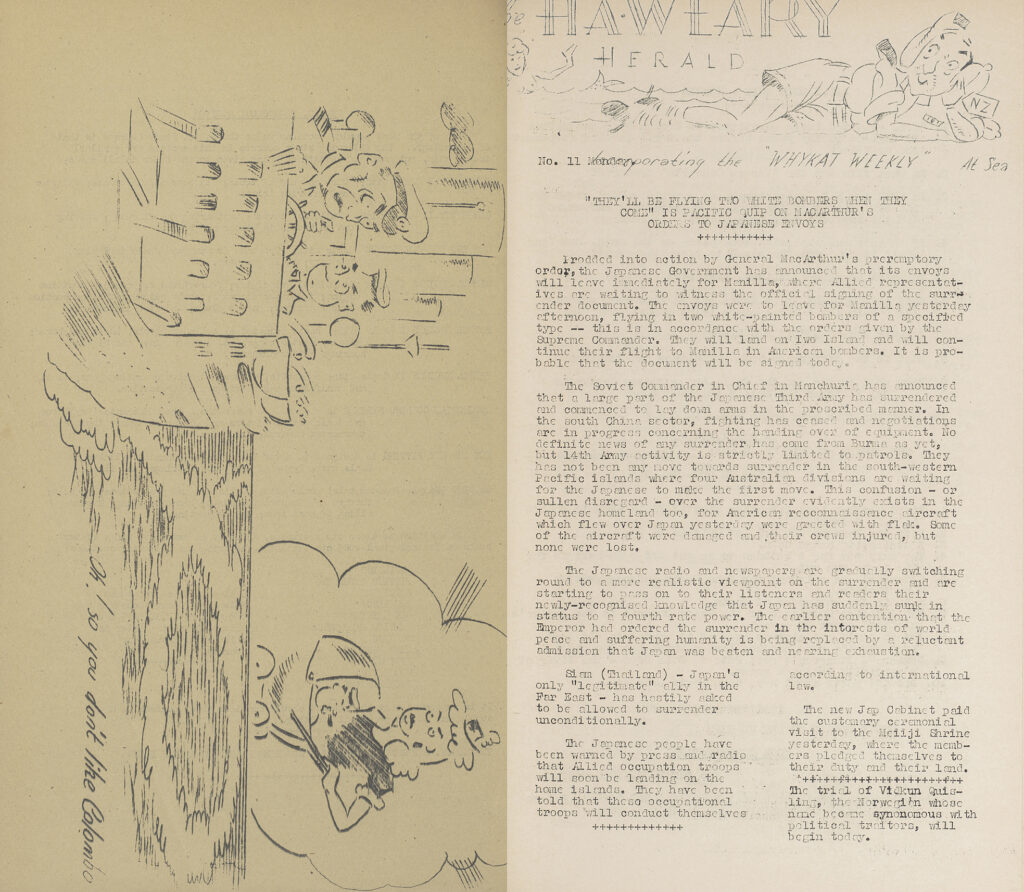

Troopship magazines represent a large and diverse type of print — many were distributed as newsletters on board ships, some were printed at ports or in camps, and others were simply chronicles or souvenirs of the voyage. However, while their location and timing of print was diverse, they share a lot of commonalities in terms of subject, tone, and theme.

The printing materials on board troopships, or even at ports of call, were very limited and this meant that while most were distributed with some regularity, they were often quite short — only two to four pages per issue.

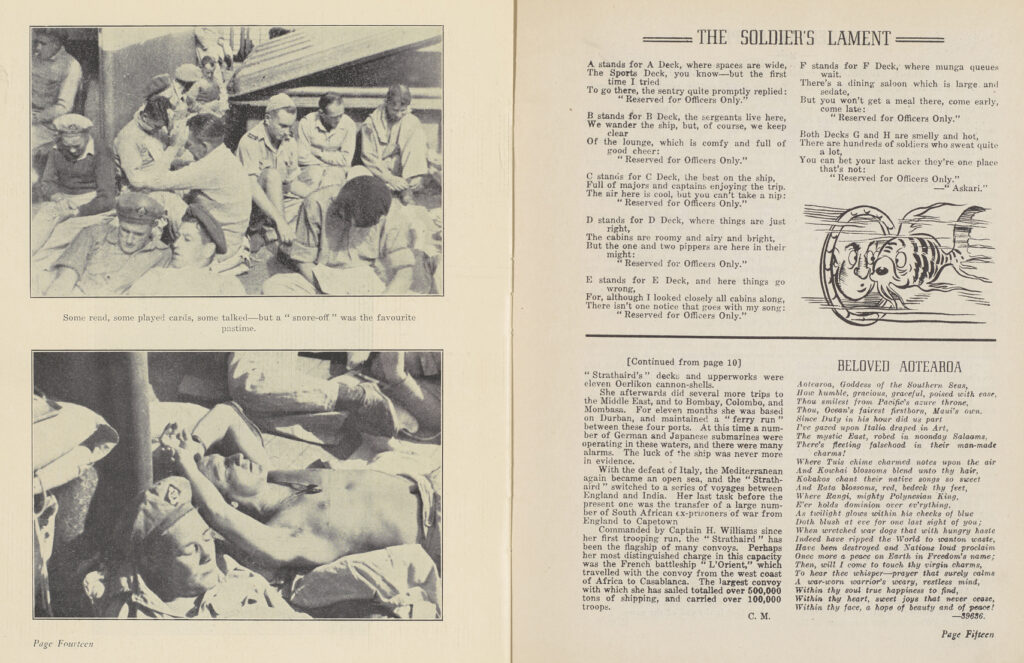

Troopships carried thousands of New Zealand soldiers to battlefields during WWI and WWII. They were crowded, confined spaces that offered little privacy or respite — and to this end it can be said the creation and distribution of the troopship magazines helped the troops negotiate their new reality of life.

Susann Liebich in Communities of Print at Sea and Beyond notes that the magazines “reflected and dealt with […] the transition from citizen to soldier, which had already begun in the training camps before the voyage [and] was further reinforced through the regulations and routines on board. [They were] emotionally and cognitively confronting an unknown future [and] the magazines put such sentiments of doubt and uncertainty into words.”

The supportive, humorous, and sometimes emboldening words within the magazines sought to solidify a sense of community; a feeling that the soldiers were not alone in their struggles and triumphs. Troopship life was uncomfortable and cramped — evidenced in the many magazines that echo this description. Writers will often commiserate about the constant noise, sea sickness, and lack of privacy that is part of shipboard life and the result of sharing quarters with thousands of men.

The magazines not only provided distraction, entertainment, and an outlet for creativity, but they now also serve as a chronicle and memento of the arduous journey and resulting war where many lost their lives. In the first issue of The Straggler’s Echo (1917), the editor comments:

“As a souvenir, this paper will be a reminder of the time spent on board and a record of the passing events, and one that, in the dim vista of the future, will conjure up recollections of this epoch in our lives.“

This material is unique because it offers a rich insight into the lives of those on board the troopships, one that is absent of propaganda unlike official histories. Evidenced by their survival and subsequent donation to Dunedin Public Libraries, the troopship magazines are highly valued by people in New Zealand and beyond.

A Source of Diversion

Boredom is often described as a major feature of military life, and this was especially true on the troopships where soldiers would spend months at sea travelling towards or back from conflict. They would spend time playing sports, listening to lectures, and training, but the magazines offered a different source of diversion that helped boost the morale of the troops.

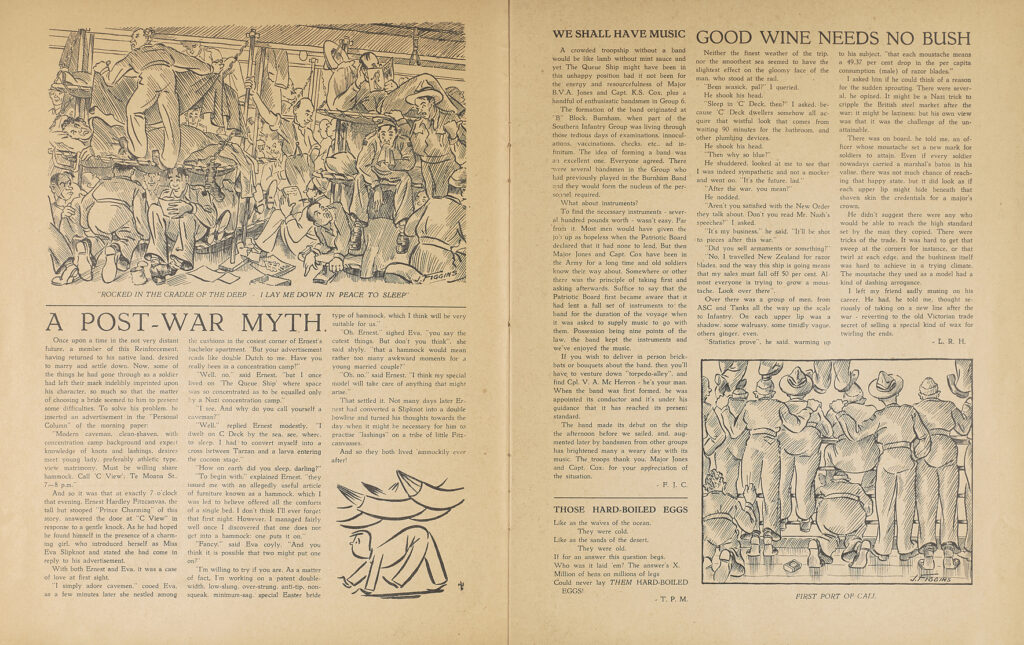

The production and design of the troopship magazines are immensely varied. Some are more amateur affairs; handwritten sheets complied in haste, while others are professional looking publications created by experienced writers and talented artists. However, all are filled with an array of content set to entertain and inform their fellow soldiers.

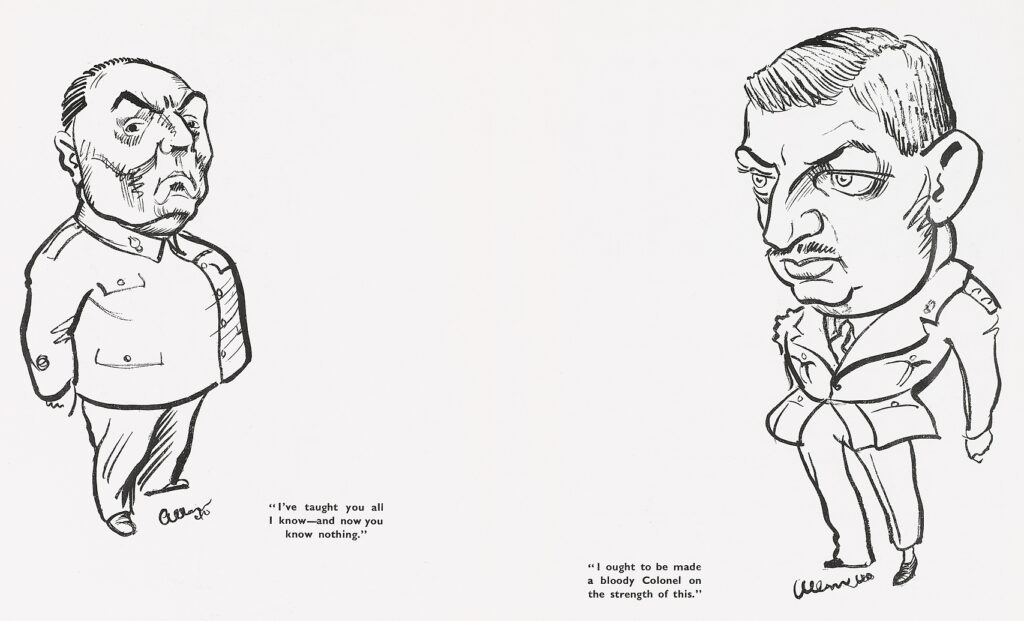

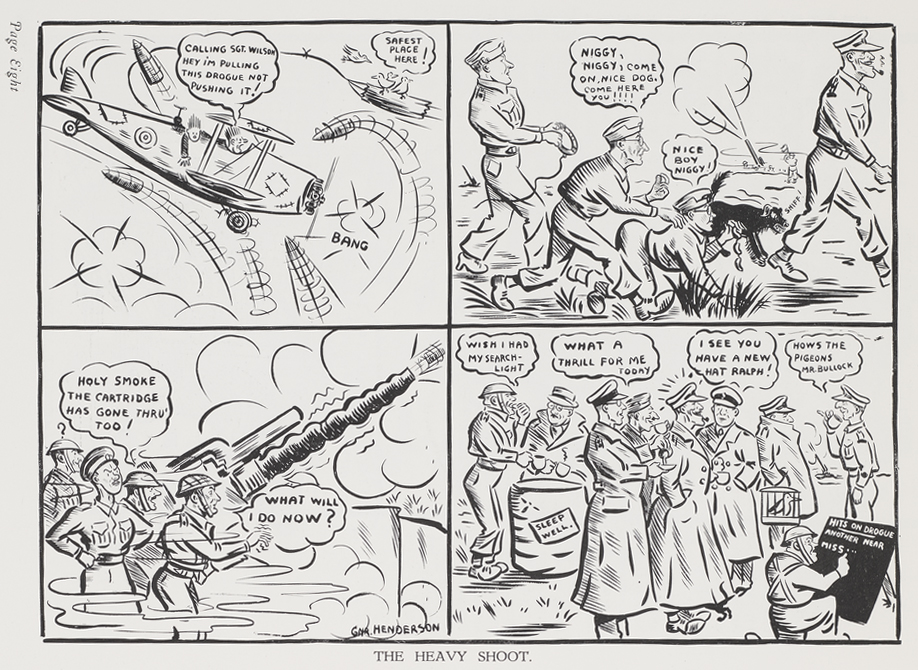

The articles, poems, and drawings in the troopship magazines were wide ranging in topic: they described the interesting places or ports visited, fond memories of home, news items or announcements, topical and practical information, and even shipboard or camp gossip. Frequently, “letters from the editor” would need to warn that the magazines were designed to entertain and that any comments or jokes about individuals should be taken in a spirit of fun.

While the magazines aimed to provide light relief and entertainment, they were also filled with topics more serious in nature, addressing sombre themes such as death, discipline, duty, and war — sometimes even describing harrowing plights for survival in the most inhumane conditions.

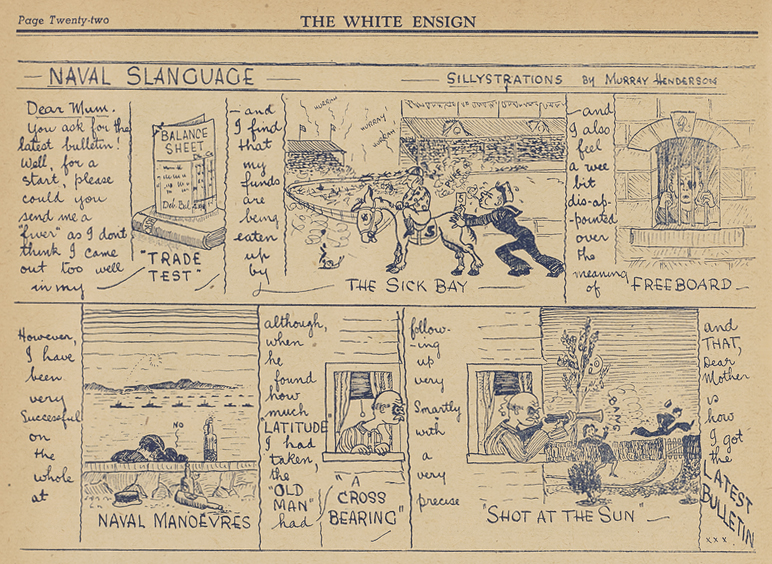

Illustrations are plentiful in many of the troopship magazines and they include cartoons and caricatures of military culture, enemy forces, or political situations.

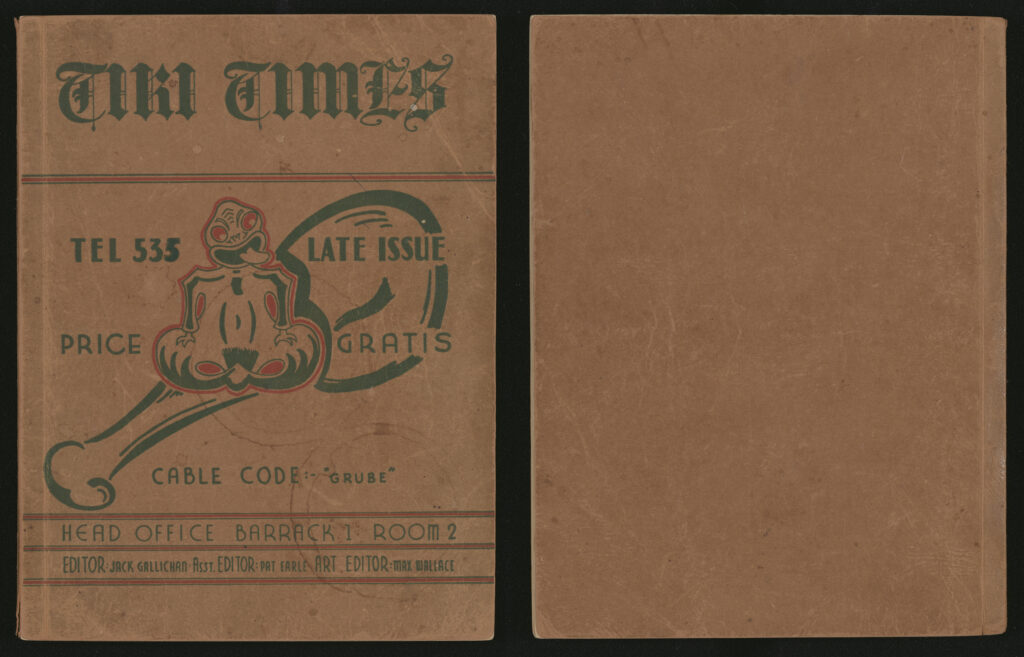

Close-up: The Tiki Times

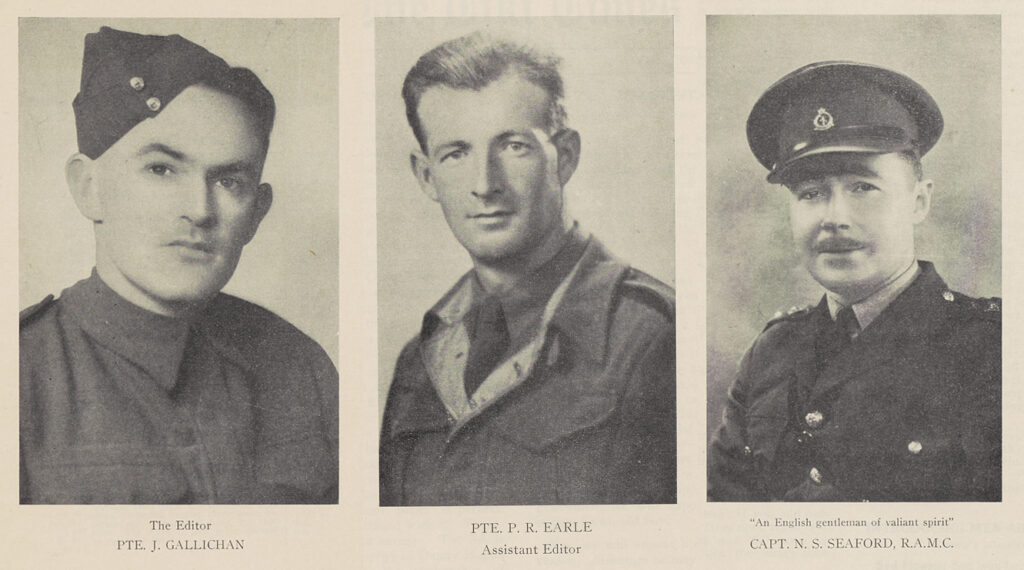

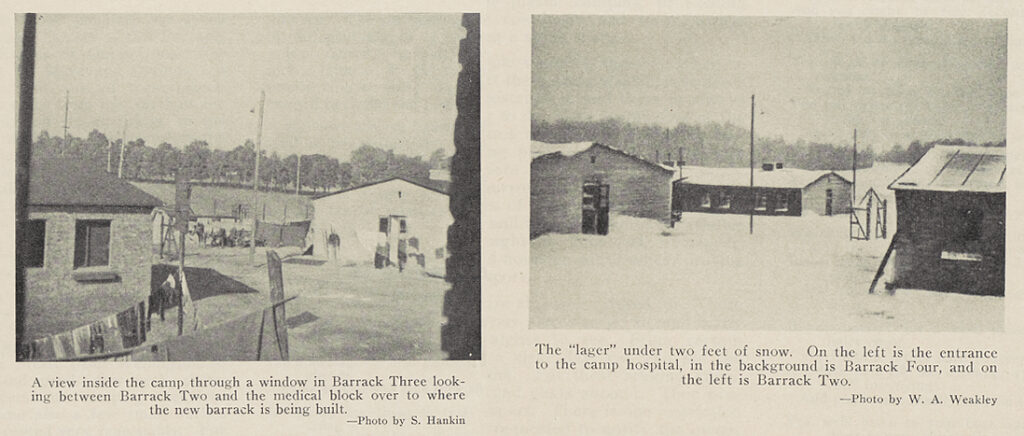

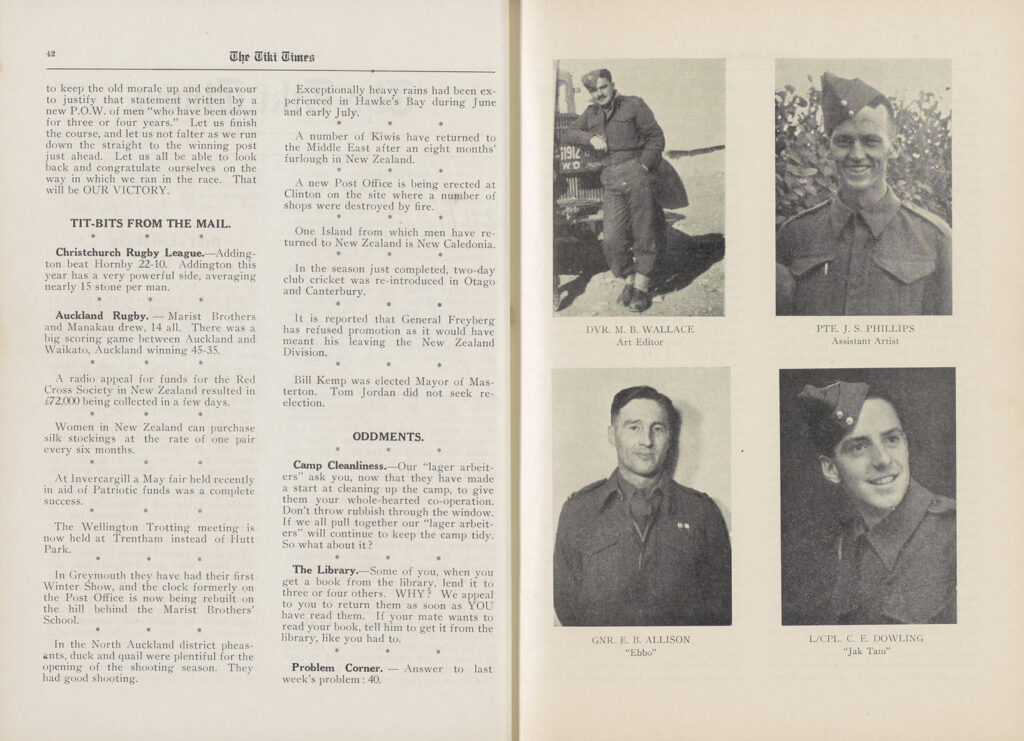

The Tiki Times was a troopship magazine produced in secrecy by the prisoners of war in camp E535 located in Milwitz, Upper Silesia, between July, 1944 and January, 1945. It was a working camp for the coal mines and over five hundred New Zealanders were held there alongside other POWs from England, Spain, and Cyprus.

The Tiki Times was first published on August 1st, 1944, and continued until January 1945, reaching twenty-four issues. Each issue was diligently archived by the editor and eventually sent back to New Zealand where it was compiled into a souvenir book. A copy was later donated to Dunedin Public Libraries’ collection.

We are instantly reminded of the cruel realities of war through the dedication inside the book, which reads:

“This book is dedicated to those of our comrades who did not return, and especially those who rest at Ettershausen in the primrose-covered valley that leads down to the Bridge at Regensburg on the Danube.”

Hand-printed in pen and ink, those creating the magazine used what materials they could find, realising that it meant a lot to fellow POWs and helped to strengthen morale. It was displayed on boards in the passage way outside the editor’s door in barrack one. Whenever the German guards made their rounds, the magazine was quickly hidden out of sight. For fear of consequences, the writers of The Tiki Times noted that they could not record their true feelings about their German captors, or risk revealing the ways they learnt to smuggle food or pretend to be injured to avoid the awful working conditions of the mines.

The editor, Jack Gallichan, describes his reasons for producing The Tiki Times in the foreword:

“It relieved in some way, the monotony and the weariness in the lives of all of us. I ask casual readers to try and picture the bitterness of POW life for themselves and to realise the part the Times endeavoured to play in its relief. This book will take casual readers into the life of a POW working camp, but it will never be able to take them into the hearts of prisoners of war where only supreme optimism could crowd out the hopelessness and bitterness of a life full of hunger and scheming, of longing and hope, and of resignation to the overlordship of a brutish foe.”

The content in The Tiki Times was diverse and aimed to help the soldiers cope with the difficult circumstances. One column was called “Introducing men about camp” and included interviews with various soldiers, described where they were from, their history, and what they plan to do after the war, etc. There were also entertaining poems, short stories, and cartoons as well as the more informative “tit-bits from the mail” that passed on headlines from New Zealand including farming news and local sports. For example, one item reports: “what is claimed to be a world’s record was established at Putaruru when a New Zealand man sheared 417 ewes in nine working hours. The previous highest number was 412.”

A regular column included in later issues of The Tiki Times was the “Epics of POW Life”, that recounted harrowing tales told to the sub-editor, Pat Earle. Two excerpts are below:

“We were in a bad condition when we were captured…We were a beaten army; we had been harried and battered, fed on false hopes… and humiliated; we were already hungry and felt the beginnings of that gnawing which blots out everything else. All prisoners of war know what it is. You have it in your dreams…”

“Thirst and exposure, pressing in on our little space, were making it too small for all of us. During the nights, which were bitterly cold, there were often fights for the warmest and driest position, fights which sometimes ended in the weaker man going overboard…” — a soldier’s experience on a raft, after their ship was destroyed by a torpedo.

Eventually, the POWs were forced to march towards Sudetenland away from the advancing Russians, and Gallichan carried every issue of The Tiki Times, together with a complete diary, for 1100 kilometres. He states in foreword:

“There came the day when we began that damnable three months march away from the Russians. It began in the dead of winter, with the glass showing twenty-five degrees below zero… I recall the friend who was murdered at Platschitz by a “posten” called Ginger because he stooped to pick up a crust of bread! Five hundred began that march, and under three hundred finished it. […] Often on the march I longed to throw the Tiki Times into a wayside ditch and so lighten my pack [but] resolved to carry it just a little further, hoping that, someday, I would be enabled to fulfil a promise.”

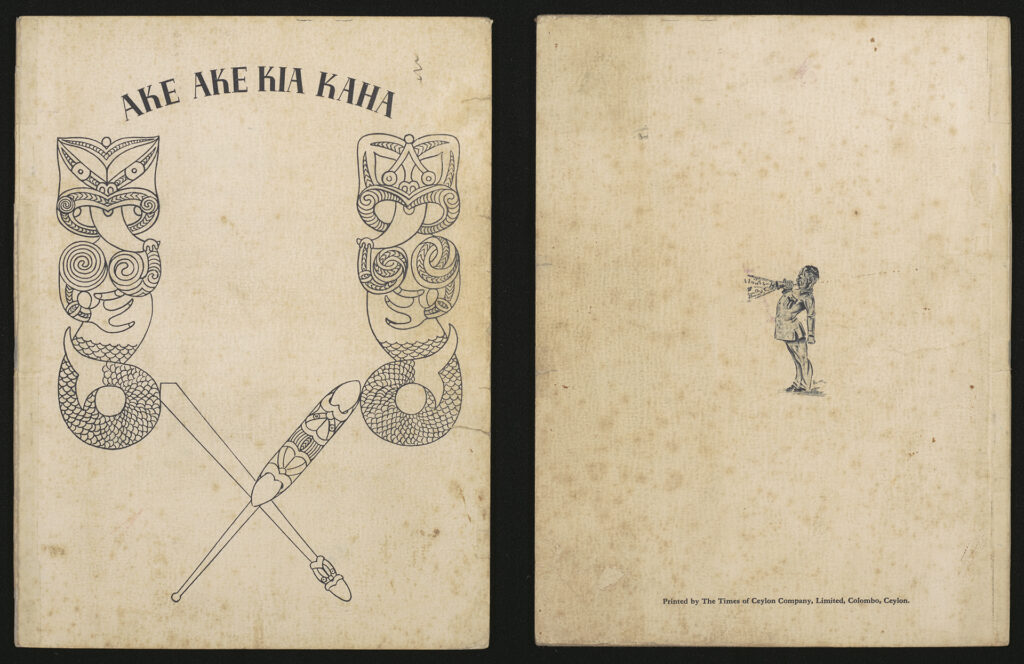

Close-up: Ake Ake, Kia Kaha

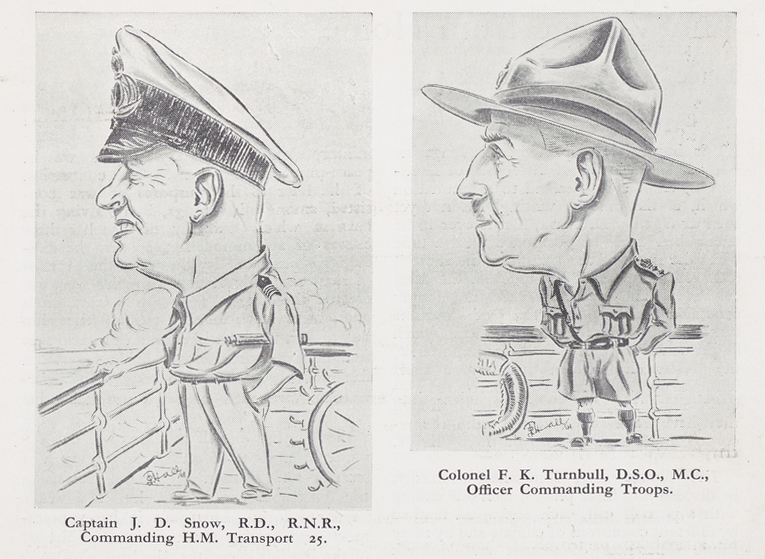

Ake Ake, Kia Kaha is the troopship magazine of H. M. Transport No. 25, and helps reveal the spirit of those of the Fifth Reinforcements, Second N.Z.E.F. exposing the variety of people that made up the unit. Similar to other troopship magazines, Ake Ake, Kia Kaha commonly published news items or announcements from home and topical and practical information for the troops, as well as more light-hearted items like humorous cartoons, poetry, gossip, and other columns designed to entertain.

The cover design takes pride of place for its creators, who describe it in the following:

“The figures represent Tangaroa, God of the Seas, and signify the importance of sea-power, making possible the safe passage of troops by sea. Māori mythology and history make plain the importance of Tangaroa as far as preparation for sea voyages, fishing expeditions and war are concerned. […] The action of the hand holding the tongue indicates the need for silence lest the enemy gain information. The paddle and the taiaha shown in the design are the weapons of the strong man. Only those tried in their use may employ them. These represent man’s progress, generosity and chieftainship, fearlessness in battle, generous and just in peace.”

Poems within the troopship magazines show what life was like on board. They functioned as outlets for the frustrations and annoyances experienced by those at sea — and ultimately, a way to find commonalities in experiences with others. One poem in Ake Ake, Kia Kaha shows how the extremes in temperature could be almost unbearable:

Tropical

Too hot to read

Too hot to sleep

Too hot to write a letter

Too hot to catch the tabby cat

For lack of something better

…Perhaps someday the heat will go

To soothe my saddened soul

But only when I’m sent below

To guard the South Pole.

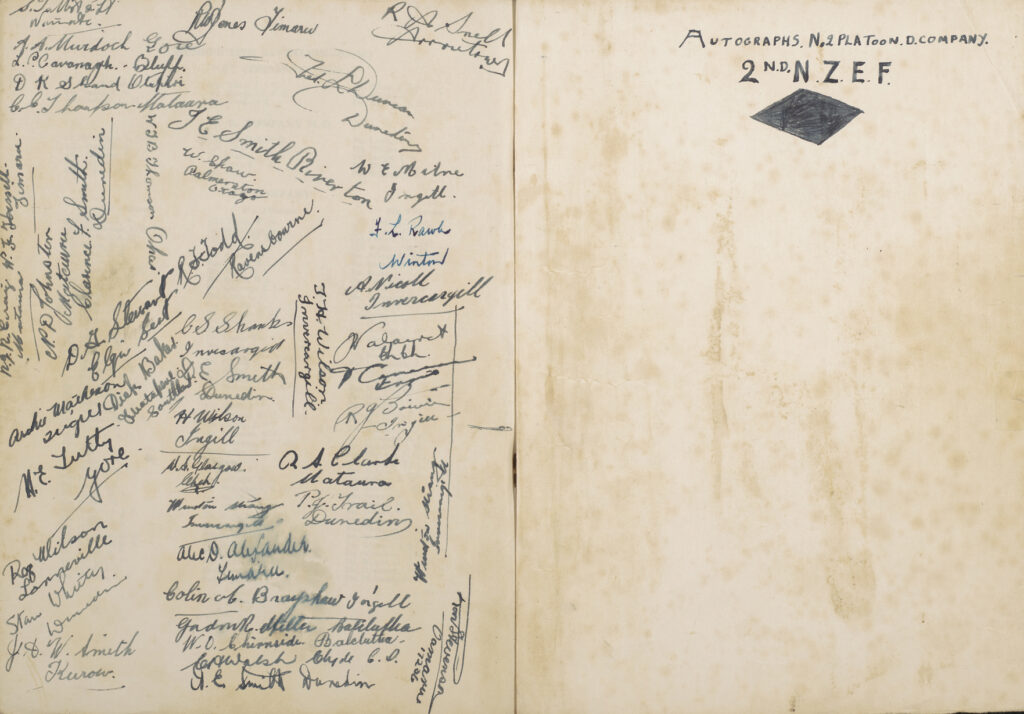

Many of the compiled issues of troopship magazines feature nominal rolls of the soldiers as well as some blank pages for autographs. This highlights their function as souvenirs, e.g., autographs can be seen at the back of Dunedin Public Libraries’ copy of Ake Ake, Kia Kaha.

Lest We Forget

The troopship magazines held in Dunedin Public Libraries’ collection provide a rich resource for anyone wanting to find out about the lives of those serving New Zealand during WWI or WWII. Importantly, they provide an element of social context and first-hand experience that is hard to find in history textbooks.

For the soldiers, the magazines provided entertainment, alleviated boredom, and helped to lift morale. They created a sense of shared hardship which fostered a sense of community and made the readers feel part of something larger than themselves.

WWI and WWII dislocated people from their homes, saw millions killed, and many more harmed physically and psychologically. It is important that their stories are preserved and able to be passed onto future generations so their sacrifice is not forgotten. Digitisation is one way that we can guarantee that our important cultural heritage items are protected.

References and Resources

- Dunedin Public Library. (n.d.). Troopships Collection. https://www.dunedinlibraries.govt.nz/heritage/mcnab/troopships-collection

- Edmonds, E. (2018, August 7). First World War Troopship and Unit Newspapers. State Library of NSW. https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/blogs/first-world-war-troopship-and-unit-newspapers

- Hoar, P. (2001). Qualitative content analysis of the New Zealand troopship publications 1914–1920. Open Access Te Herenga Waka-Victoria University of Wellington. https://doi.org/10.26686/wgtn.17005531.v1

- Liebich, S. (2021). Communities of Print at Sea and Beyond: Troopship Magazines in World War I. Shipboard Literary Cultures, 211–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85339-6_9

- Liebich, S., & Publicover, L. (2021). Introduction: Shipboard Literary Cultures and the Stain of the Sea. Shipboard Literary Cultures, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85339-6_1

- Massey University Library. (n.d.). Troopships. https://tamiro.massey.ac.nz/nodes/view/945

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. (2020, April 16). Anzac Day, https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/anzac-day/introduction

- Snee, J. (2015, June 5). NZ troopship magazines from the First World War. Auckland War Memorial Museum. https://www.aucklandmuseum.com/discover/collections/topics/nz-wwi-troopship-magazines

- Tauranga City Libraries. (n.d.). Aquitatler (1942). Pae Korokī. https://paekoroki.tauranga.govt.nz/nodes/view/21162